Start-up organizations provide an extraordinary example of chaos organized into manageable chunks. Perhaps more than anyone else, the individuals who comprise a start-up team are required to understand their team’s goals across a variety of disciplines — research, marketing, design, development, architecture, etc. — as well as their own responsibility to move the company’s overarching objective forward. Entrepreneurs must choose the direction, designers must think through the options, and developers must cull a functional product or service, all while giving feedback to and receiving it from their colleagues.

At least, that’s the idea. Most start-ups tend to take liberties somewhere along the way. Some start-ups begin with a novel business model, whereas others begin with a beautiful design. Still others try to test things out first with a functional prototype, even if it is a bit ugly. All of them — regardless of their initial approach — adapt their process over time in order to create a well-rounded product or service. And for this reason, most of today’s start-ups describe themselves as “agile.â€�

Agile start-ups, as the name implies, should be capable of changing their design, development and/or business objectives on a dime. This is much easier said than done — especially for today’s user experience designers. The user experience (UX) designers who work at agile start-ups are required to do two things exceptionally well: (1) grasp the intent of the product or service being developed, and (2) effectively communicate those good intentions to end users in a language they’ll understand. Neither of these is as straightforward as it might sound.

Ideally, designers will jumpstart their design process by carefully selecting well-reasoned entrepreneurs to work with; but what happens when the designer is altogether alien to the community he is designing for? The breakneck speed of agile start-ups makes it incredibly difficult for designers to craft appropriate messages to their audience at large. Only by understanding the processes and opinions that dominate start-ups can designers begin to reach out and make a difference for the end users of their product or service.

User-Centered Design, Sans User

Designing with a clear idea of who the users are has never been simple. Most designers who have experience with the trial by fire known as a “lean start-up� will almost vehemently agree: because there are more than a few fires to fight, adopting a big-d Design process at start-up organizations is, simply put, exceedingly difficult. Invariably, this means that most start-up organizations devolve to the point that salability reigns supreme, or form trumps function. But whereas flexible, agile environments are very good for getting those things done, good design takes time, which makes the design process of start-ups almost universally hamstrung.

Keep the levels of UX in mind. (Image: Jon and Barb)

In short, agile, user-centered design tends to ignore the aesthetic, intangible, ambient qualities that good experiences are all about. As a consequence, budding artistic directors, brand ninjas and interaction designers have been apt to worry. Without the ability to intimately understand the audience for whom they’re designing, these team members can’t do their jobs. The logical question becomes, how can they? How can designers effectively communicate with an audience they’ve yet to meet?

The textbook definition(s) of UX design yields some clue. User-centered designers are encouraged to perform design research and then create personas as well as other deliverables. Certainly those would spotlight the factors that affect a company’s relationship with its users… right? Perhaps. While research is undoubtedly necessary to the design process, its deliverables are not.

I’ve written before that designers should bootstrap their own culture of UX within an organization. In this article, I’ll take that idea one step further: in order for a start-up to effectively communicate with its target audience, a spirit of empathy must pervade its every design decision — empathy cultivated by engaging in an ongoing, outward, user-centered conversation.

Where Has All The Empathy Gone?

The task of any designer who works in a start-up environment requires empathy. The designer, perhaps more than any other team member, must empathize with stakeholders (to understand the project’s business objectives), developers (to understand its technical requirements) and, of course, users (to understand the nature of the problem they’re solving), all at once. Designing with consideration for all three parties effectively frames their strife.

Valuable though it may be, however, most start-up environments discourage empathy. Consider the number of times you’ve heard something like, “We’re targeting wealthy single males, ages 45 to 55,� or “We’re just like Amazon, but for baby boomers.� Well, that’s just great. A product description like that might initially help a team grok (a word that, ironically, means “understand by empathy�) an idea, but as far as rhetoric goes, merely saying that you know what segment you’re targeting isn’t enough.

Every e-commerce company sells products. Newcomers to the space can, and often do, learn a lot by studying the desire paths paved by industry notables (indeed, entire books are written on the subject). But let’s be clear: “I want to be Amazonâ€� doesn’t imbue the designer with empathy. Creating something that looks and feels like Amazon will, of course, look and feel like Amazon. If that website is then marketed to a wholly different crowd, then the resulting outfit will be disingenuous — the polar opposite of empathetic.

In order to create something real, unique, of lasting value and with a look and feel of its own, members of start-up teams must vacate their cubicles.

One… Erm, Three Processes

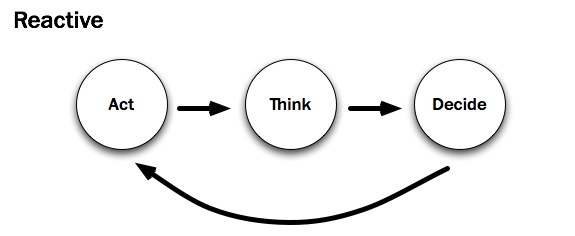

Adding to this perceived resistance are the various processes that drive start-up organizations at any given time. A recent blog post by Whitney Hess contrasts three specific types. It’s worth noting that all of the approaches detailed below show the exact same verbs in the exact same sequence. What’s different in each is the primary action that drives change along the way.

To cite Hess:

I see a lot of products developed using the Reactive Procedure:

- I’m scratching my itch.

- Should I keep scratching this itch?

- I’ll scratch this other itch.

As a designer who frequently consults with agile start-ups, I concur with Whitney’s sentiments: the reactive approach (“build it and they will comeâ€�) is far and away the most common. There is, of course, a good reason for all that action: development drives change. Start-ups act in order to build an initial prototype. Prototypes, in turn, move the company — indeed, the user feedback loop — forward.

Unfortunately, the prototypes developed by most start-ups exhibit a keen lack of consideration. Who is the prototype targeted at? 40 to 50 somethings? There are certainly a lot of them. Will those 40 to 50 somethings be able to grok it? That is, will users be able to tell what it’s “all about� from the design? Because this kind of subjectivity is incredibly nebulous, prudent start-ups rely on experienced UX designers to help them uncover the answers. It’s no wonder that Whitney and I see this in our line of work.

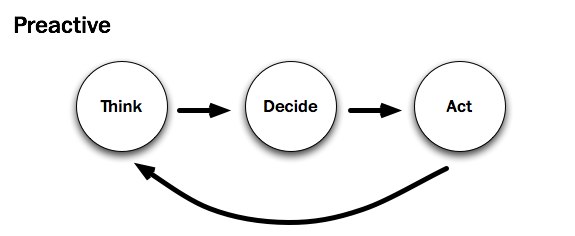

As a user experience designer, consultant and member of the New York tech community, I instead advocate for using the Preactive Procedure:

- Who’s itchy?

- That itch isn’t being scratched.

- This is how to scratch that itch.

I believe that most UX designers would agree — dare I say, empathize — with Whitney’s prescribed preactive approach. Beginning with thinking — with research — is in a user-centered designer’s blood; it helps them understand their audience and voice their messages appropriately. Further still, “preactivityâ€� appears to be the only real way for designers to gain empathy. But most start-up environments run counter to this approach. Acting and then thinking usually leaves little room for the voice of research. Has Whitney encountered a start-up that tries to reconcile the two?

As luck would have it, she has. Whitney recently worked with an entrepreneur who marches to a different beat:

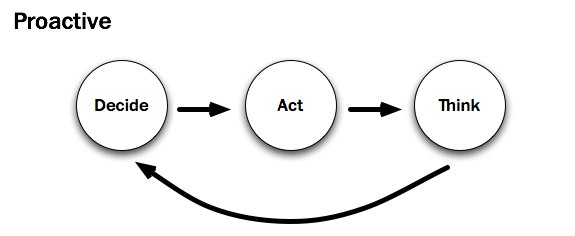

Campbell McKellar, founder of Loosecubes, is the first person to make me realize that there’s something even better than the Preactive Procedure — the Proactive Procedure.

By acting sooner, you are actually achieving more. You are creating the future instead of just predicting and accommodating for it. You are inventing a new reality, based half in what people need, and half in what you want them to have. You can observe behavior sooner and course-correct. It is the most transformative of all three procedures for both the subject and the object.

An entrepreneur at heart, I want to agree here, too. The proactive process appears to be a viable alternative to the unenviable tension between designers and developers at start-ups. But just because a group is humming along with a decision-based proactive process doesn’t mean that the organization’s designer understands its users any better. By UX standards, this process almost seems to disenfranchise them: it moves “thinkingâ€� — and here, I presume, research — all the way to the back of the bus.

In sum, it’s easy to envision scenarios at a start-up in which a given development process proves more valuable, more productive, than its alternative. Should the team think, act or decide? It depends. Regardless, as designers join start-ups, they’re very likely to find that design is secondary to the process unless, of course, their organization follows a preactive process. But for most start-ups, that’s simply not the case.

In order for an organization to learn more about its users, the design-minded members must advocate to that effect, changing the way that design is approached. Designers must stand up for their part of the process. As UX designer Joshua Porter attests, “The further a designer is from the people they’re designing for, the harder it is to design for them.�

Start-ups — or more specifically, the designers at start-ups — need to get as close to users as they can. Product development can’t rest in the entrepreneurs’ and/or the developers’ hands alone.

Why Design Fails

When asked, most designers don’t take long to provide honest, valid reasons why the design process is important to developers and entrepreneurs alike. There is firm precedent to that end, and they are designers by choice, after all. But just because the truth and beauty of good design is evident to most designers doesn’t exactly mean that their colleagues share their sentiments.

If it isn’t making Dollars… (Image: Kristian Bjornard)

Start-ups — and more importantly, the individuals who comprise them — have a great number of mental hurdles standing in the way of their empathy with end users. The aforementioned quickened pace and changing processes aside, here are those hurdles:

- Start-up teams have strong convictions.

Anyone who believes strongly in a cause (be it an idea or a Web application… or both) will identify with it. If a designer questions the validity of an idea, then they are questioning the team. This is a difficult, integral part of the design process. - Research doesn’t (immediately) sell.

It doesn’t take weeks of research to sell a product to someone, and given enough time a good marketer can sell anyone almost anything — especially something beautiful. As a consequence, team members are likely to judge the design book by its cover. Research rarely affects their notion of beauty. - Start-ups trust results they can measure (preferably in dollars).

Web metrics are currently the bread and butter of today’s Web-savvy marketers. Saying that a design is good is one thing. Saying that a design has increased conversions by 200% is another. Attaching a number to something makes entrepreneurs (and, yes, designers, too) feel better about the problem being addressed. If the current process is measurable, should an up-front design process be allowed to slow that down?

In sum, short-term, yes-or-no, go-or-no-go (Decide! Act!) thinking pervades the start-up space. The reality is that most agile start-ups favor a “design-less� process. While UX designers might trust that empathy (or understanding) is tantamount to a start-up’s success, their teammates won’t necessarily believe so. In order to effect change, designers must fight for the integrity of their design from the inside out.

Leading The Way With Empathy

To be clear, good design doesn’t come about at start-ups just by studying the metrics generated from a prototype or by talking to users through a proxy — say, support emails. That isn’t to say that these things aren’t valuable — they certainly can (and often do) point to the consequences of prior decisions. But feedback, by definition, cannot determine the company’s next — or, more importantly, first — steps. There’s the rub. Unfortunately, that is the problem routinely faced by start-up designers.

No one would argue that determining what’s “good� for a Web design is subjective, which makes it a frightening prospect. As D. Keith Robinson wrote on A List Apart all the way back in 2005:

Knowing what people want on the Web can be hard. You either need to have incredible empathy or have done fairly extensive research. This empathy I’m talking about, in my opinion, can really only be built up over time observing all kinds of people doing all kinds of things on all kinds of websites and applications. Even then, as you move from project to project, the people, problems and needs change.

With every new project comes a new target user, a new person to empathize with. And just as with meeting a new person, understanding what they like and don’t like takes time. If designers are to appeal to this new person, they first have to get to know them. As both Whitney Hess and Cennydd Bowles have asserted, focusing on a rapid proactive process — decide, act, think — gives most start-ups a solid plan of attack. Not only do teams get to test market viability first, they can then think about how they’ll differentiate the product shortly thereafter.

Yes, this process makes brand-conscious designers uneasy, and understandably so. In the beginning, though, without the context that a prototype creates, designers must lean towards the relatively “safe� side, where all interaction design begins: buttons look like buttons, drop-downs look like drop-downs and perhaps even the names of start-ups sound like start-ups. Robert Hoekman, Jr. calls this Designing the Obvious. I call it designing the boring bits.

Because what this approach makes up for in usability, it certainly lacks in propriety. To determine what’s appropriate (which is subjective), designers must conduct field research.

Hold Your Own Convictions

Plenty of UX designers preach preactivity; they are the ones who want to understand — to empathize with — their audience and build something tailored to them. Moreover, these designers have the relative luxury of working within organizations. For them, Cennydd Bowles and James Box have written a lovely book, Undercover User Experience Design. If you’re at a company where design is ailing and you want to fix it, I suggest picking up a copy right away.

If you’re an independent consultant or a designer working with a start-up that’s out to craft the best possible experience, then I would suggest a couple of things, all centered on the same concept, which is to make listening a part of the company’s design process:

- Create a design strategy.

Articulate who you’ll be designing for (even if they’re only make-believe) and how they’ll use the website. I’ve written before how I do this. Regardless of how you do it, know who you’re trying to know. - Have a solution.

Work with a development team to generate a quick prototype that demonstrates your best (albeit uninformed) solution. Have at least two people use the prototype the way it is intended to be used. Befriend them, and see if they’ll contribute feedback as you refine your vision. - See for yourself.

Finally, and most importantly, see for yourself. Visit your users in their natural environment, and make sure their concerns are addressed. If you’re in a position to do this, ask them questions related to the problem your start-up addresses.

In all cases, start-up designers should center their design process on listening to users. Instead of speaking to users by way of the design, converse with users to inform the design. Empathy, the human connection, makes or breaks an informed experience.

Because most of us work behind computers for hours, days or weeks at a time, gaining empathy is obviously easier said than done. However, empathy is the only way to turn a good business idea into a well-articulated design conversation. Respect is earned, a brand is born, when every interaction that an organization has with its users is open, earnest, honest and, most of all, appropriate.

Related Resources

- Getting Real About Agile Design, Cennydd Bowyles on A List Apart

- Personas and the Advantage of Designing for Yourself, Joshua Porter on Bokardo

- The Complete Beginner’s Guide to Design Research, Andrew Maier on UX Booth

- Our Misguided Focus on Brand and User Experience, Jon Kolko

- Empathy and Web Design, Janko Jovanovic

- Giving Users Some Credit, Jeremy Girard on Design Informer

- “CopyCat Design� and “UX Won’t Save You,� 52 Weeks of UX

- Alan Cooper’s keynote, Agile 2008

- Usability Experts Are From Mars, Graphic Designers Are From Venus, Curt Cloninger

- Personas?, Ask 37signals

- 5 Design Decision Styles. What’s Yours?, Jared Spool on UIE.com

(al) (sp)

© Andrew Maier for Smashing Magazine, 2011. | Permalink | Post a comment | Smashing Shop | Smashing Network | About Us

Post tags: usability, ux