Another year, and another blog post (singular). Oh well. I always have aspirations to publish more! But you know, one of the joys of being semi-retired is not having to do anything. You know, it’s been a hard few years. So I tried to take it easy on myself in 2022. I spent a lot of time exploring, a lot of time reflecting, and a good bit of time just doing whatever felt right at the time.

Recently I’ve been reflecting on some of my favorite things from last year. Maybe as a way to focus on the positive. Maybe as a way to keep track of time in our time sick world. Maybe just to get back into the habit of writing. So here’s some of my favorite reads of 2022.

Books

I really enjoy reading, but this year I kind of gave myself a pass on anything too serious — mostly sticking to my trusty home base of science fiction.

Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s This is How You Lose the Time War

From the publisher:

Among the ashes of a dying world, an agent of the Commandment finds a letter. It reads: Burn before reading.

Thus begins an unlikely correspondence between two rival agents hellbent on securing the best possible future for their warring factions. Now, what began as a taunt, a battlefield boast, becomes something more. Something epic. Something romantic. Something that could change the past and the future.

I fucking loved this book. I started it based on a recommendation from a friend, and didn’t really look into it much before I started. This book is much less about the plot (which is a play off The End of Eternity) and more about the writing and world building. The best way I could describe it is a spy story told through love letters in a poetic universe.

Think of birds as a comms channel I can open and close seasonally; fellow operatives relate their work to me at the equinoxes; Garden blooms more brightly in my belly. There’s enough traffic that it’s a simple matter to disguise incoming and outgoing correspondence, misdirect, hide in plain sight.

It’s also a short read, which was a nice breath of fresh air after finishing off the Dune series prior to picking this one up. I have a feeling this is going to be one of my most recommended books going forward.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendevous with Rama

From the publisher:

An enormous cylindrical object has entered Earth’s solar system on a collision course with the sun. A team of astronauts are sent to explore the mysterious craft, which the denizens of the solar system name Rama. What they find is astonishing evidence of a civilization far more advanced than ours. They find an interior stretching over fifty kilometers; a forbidding cylindrical sea; mysterious and inaccessible buildings; and strange machine-animal hybrids, or “biots,” that inhabit the ship. But what they don’t find is an alien presence. So who–and where–are the Ramans?

I’d never read the Rama books before, so when I heard that Denis Villeneuve was going to be tackling Rendevous with Rama, I took the opportunity to read the whole series (Rendevous with Rama, Rama II, The Garden of Rama, and Rama Revealed).

Rendevous with Rama is a fantastically Clarke book. A team of highly trained professionals all work together to explore a mysterious object in space. Does much more need to be said? This book went down like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. My only criticism is that it left me wanting for was more.

Rama is a cosmic egg, being warmed by the fires of the Sun. It may hatch at any moment.

And unfortunately, there is more.

Clarke teamed up with Gentry Lee to write three more novels — Rama II, The Garden of Rama, and Rama Revealed and I all I can say is: I do not recommend them. They are upsetting in very odd child-bride wedding night kinds of ways.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Elder Race

From the publisher:

A junior anthropologist on a distant planet must help the locals he has sworn to study to save a planet from an unbeatable foe.

I loved Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time, so when I heard Jason Snell offer up Elder Race on The Incomperable, I decided to give it a go. I absolutely love the premise of this book. It’s a singular story told from two different viewpoints, one of them science fiction, and the other fantasy — both happening in parallel — because the two main characters don’t share enough dialect to explain themselves to each other.

They think I’m a wizard. They think I’m a fucking wizard. That’s what I am to them, some weird goblin man from another time with magic powers. And I literally do not have the language to tell them otherwise. I say, “scientist,” “scholar,” but when I speak to them, in their language, these are both cognates for “wizard.” I imagine myself standing there speaking to Lyn and saying, “I’m not a wizard; I’m a wizard, or at best a wizard.” It’s not funny.

And who doesn’t love an old, cranky wizard anthropologist?

Miles Cameron’s Artifact Space

From the publisher:

Out in the darkness of space, something is targeting the Greatships.

With their vast cargo holds and a crew that could fill a city, the Greatships are the lifeblood of human occupied space, transporting an unimaginable volume - and value - of goods from City, the greatest human orbital, all the way to Tradepoint at the other, to trade for xenoglas with an unknowable alien species.

This was another recommendation from a friend, and I’m glad I picked it up. At it’s core, it’s about highly competent people all working together, pushing their limits, and achieving success. It’s the kind of genre someone once described to me as competency porn — Star Trek: The Next Generation being the ultimate example.

There was very little drama in Space Operations. In fact, every station projected an elaborate aura of calm, as if they were competing to be dry and emotionless. No one swore, no one spat, no one was angry or afraid. Nbaro loved it.

This book pulls from a lot of familiar ideas — the Greatships are an obvious call back to Battlestars, while a lot of the socialist themes call back to Star Trek’s economy. My biggest criticism of this book is the maddening way Cameron switches back and forth between using character’s first and last names — even within the same scene! It makes it incredibly difficult to keep track of who is who with such a large cast, and toward the end I caught myself not even remembering who a certain person was.

Dennis E. Taylor’s Heaven’s River (Audiobook)

From the publisher:

More than a hundred years ago, Bender set out for the stars and was never heard from again. There has been no trace of him despite numerous searches by his clone-mates. Now Bob is determined to organize an expedition to learn Bender’s fate—whatever the cost.

The Bobiverse is probably my favorite audiobook series of all time. It’s all a part of a grand space opera spanning the galaxy… but also pretty sarcastic and silly? Ray Porter does an amazing job of narrating these books, and is a large part of why I enjoy them so much.

Heaven’s River finds a way to pull the series back from the infinite and focuses back down on a single planet for a great little beaver adventure.

Well, space beavers.

Even More Books

Neal Stephenson’s Termination Shock: Okay, I actually like Stephenson, and this is a very good book about the inevitable future of Geoengineering and it’s political consequences. Coupled with a very weird Queen fetish. It’s weird. Weird enough to take away from the story line. But if the climate angle of the book interests you — I highly recommend After Geoengineering as a follow-up.

Baoshu’s The Redemption of Time: A semi-official 4th book of the Three Body Problem. This is a great continuation of the series, and a good way to answer some lingering questions about the Trisolarians.

Frank Herbert’s Heretics of Dune (Dune 5): I was a little shocked at how much I loved this book. I mean, I love Dune. But this one ended up being one of my favorites of the series. Great new characters, new technologies, and a whole new set of powers for the Atreides genetics.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time: This was actually a re-read in preparation of reading Children of Ruin and the upcoming Children of Memory. What can I say? It’s one of my favorite science fiction books of all time — even if only for the worldbuilding. Sentient spiders? Sentient spiders!

Newsletters

Alex Steffen’s The Snap Forward

From Discontinuity is the Job:

To be alive right now is to find ourselves flattened against the fact that the entire human world—our cities and infrastructure, our economy and education system, our farms and factories, our laws and politics—was built for a different planet.

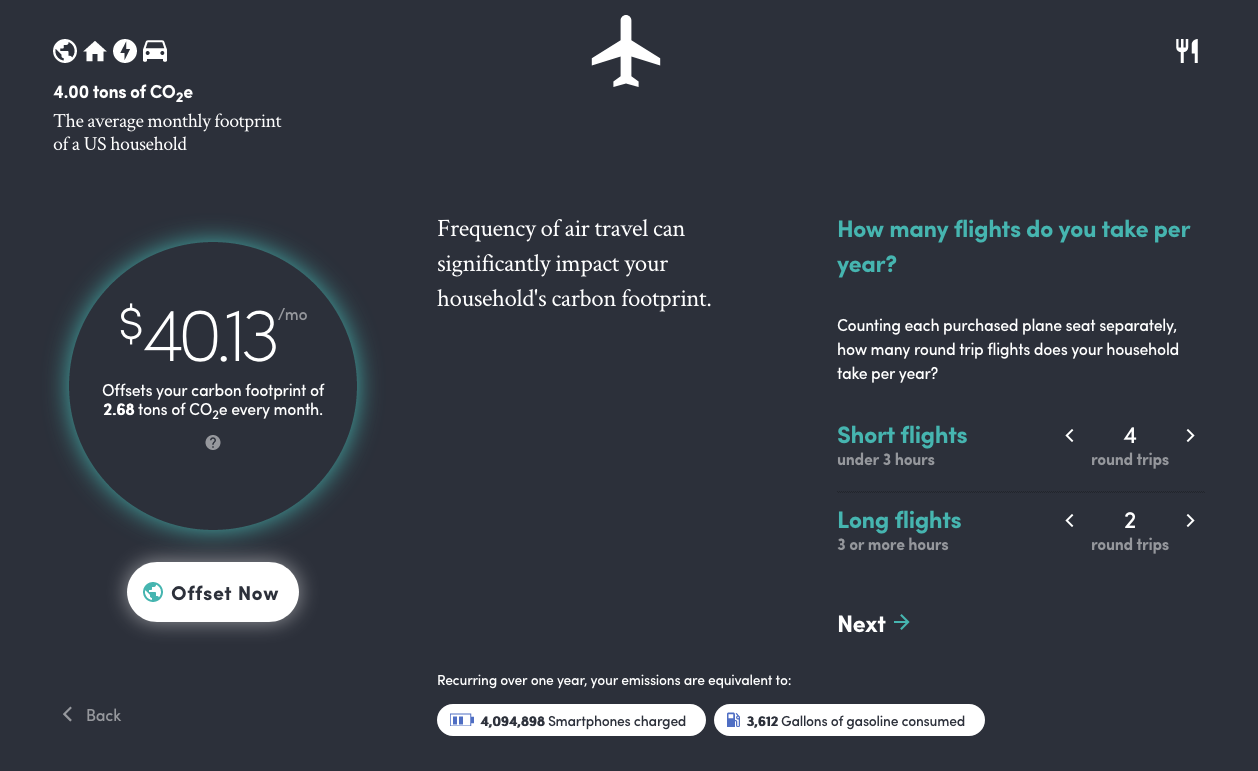

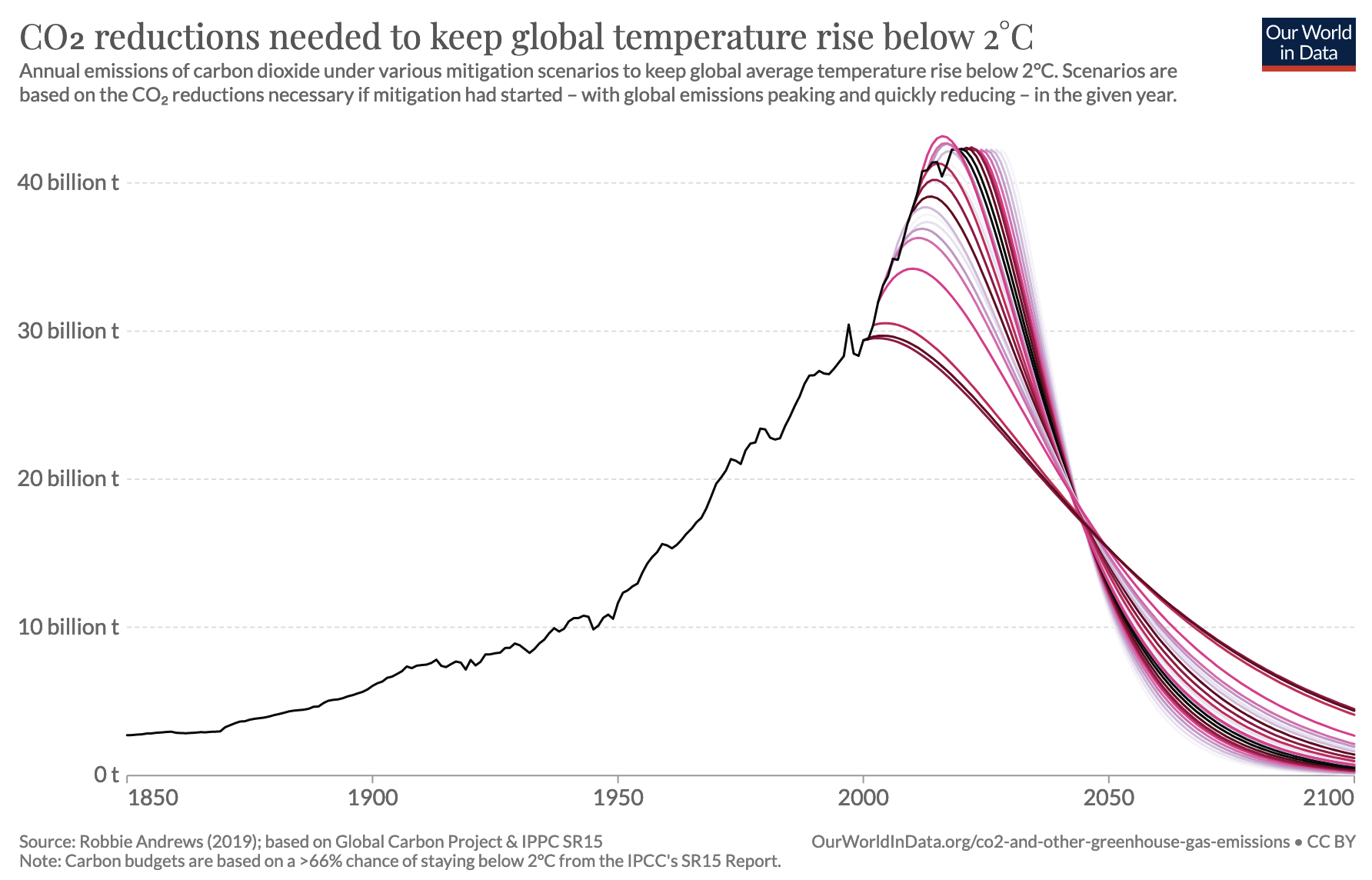

I can’t remember exactly how I stumbled on Alex Steffen’s The Snap Forward but the idea instantly clicked with me. His newsletter focuses on how climate has affected our infrastructure, our society, and our relationship to the world. I love his newsletter because it makes me feel more sane in a world that keeps trying to sell a new carbon offset marketplace as the solution.

From Tempo, Timing, and the Translucence of the Future

The tempo of change, and our refusal to acknowledge its acceleration, has turned our visions of continuity, stability and value into fantasy worlds. We’re cosplaying people who live in past decades before discontinuity ate our societies.

I wouldn’t classify The Snap Forward as doomerism, either. It’s a focus on accepting the world as it is and looking for solutions within that framework. Even if all emissions were cut to zero tomorrow, we’d still be facing a myriad of very challenging futures. What do we do with that knowledge? How do we prepare for the transapocalyptic now?

Matt Levine’s Money Stuff

I’ve been reading Money Stuff for a few years now, and I can’t really put my thumb on why I love it so much. Sure, it’s about finance… but kind of the weird stuff in finance. More about the cogs of the machinery and the weird personalities in the news than it is about whether the S&P 500 is going to go up or down next week.

From FTX’s Balance Sheet Was Bad:

But then there is the “Hidden, poorly internally labeled ‘fiat@’ account,” with a balance of negative $8 billion. I don’t actually think that you’re supposed to subtract that number from net equity — though I do not know how this balance sheet is supposed to work! — but it doesn’t matter. If you try to calculate the equity of a balance sheet with an entry for HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT, Microsoft Clippy will appear before you in the flesh, bloodshot and staggering, with a knife in his little paper-clip hand, saying “just what do you think you’re doing Dave?” You cannot apply ordinary arithmetic to numbers in a cell labeled “HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT.” The result of adding or subtracting those numbers with ordinary numbers is not a number; it is prison.

It’s an understatement to say I don’t love finance, but I do enjoy me some Money Stuff.

What’s Next?

I’ve really been enjoying re-visiting some of my favorite authors and finishing off big series I never quite got around to. Last year I finally finished off the whole of Frank Herbert’s Dune (never having read 5 & 6 before), and this year I’m getting the itch to do the same for Foundation. To be frank, I don’t even remember where I ended with that series. But it does feel like a good opportunity to maybe just re-visit the entirety of the Asimov Universe… in chronological order. I’m also getting a terrible itch to revisit a bunch of Vonnegut’s work after watching the excellent Unstuck in Time. But I like new authors too!

I’m also interested in finding more books and newsletters about… I guess you’d call it urban design. Stuff like Strong Towns and other sources of how to adapt our cities into resilient communities. I actually have background in city planning from my Civil Engineering days, but I feel like there’s been a big surge in new thinking that goes farther than the YIMBY/NIMBY noise of the past decade.

Have some recommendations? Hit me up on Mastadon: @kneath@indieweb.social.