One of the most important responsibilities for managers in tech companies are having regular one-on-ones with their team. The idea is to meet with each member of the team once every week or two, face-to-face, to talk about whatever the team member wants. And the face-to-face part is crucial. Our brains process an immense amount of information during a conversation — eye contact, facial expressions, intonation, body language — everything that’s beyond the content of our words (what an email might convey). This information trains our intuitive reasoning, building understanding and perspective — allowing us to better understand what the other person means when they say something.

Yet there is an entire class of managers in software today that avoid face to face interaction with those they manage: product managers. It’s common for a product manager to be running multiple experiments every week, but how common is it for a product manager to spend face time with multiple customers every week? Why is that?

The vibe I get from our industry today is that product managers believe measurable data and analytical reasoning are king and result in superior decisions. Many even believe with enough effort, they can measure emotion. They see emotions in their analytical world view: as a (difficult) metric to be measured, tested, and improved. This is how we end up associating ideas like Churn (an artifact of your billing data) with an emotion like Frustration (something a human feels). But emotion can’t be measured, it must be felt.

I recently listened to a great Planet Money episode on Spreadsheets! that discusses the history of spreadsheets and how it’s changed the way we make decisions. The episode was inspired after an article written in 1984 about the significance and danger of the advance of spreadsheets:

The spreadsheet is a tool, and it is also a world view — reality by the numbers.

— Steven Levy on A Spreadsheet Way of Knowledge

Many of us don’t use spreadsheets today, but we do use tools that came from spreadsheets and promote the same world view. We compare competing Facebook events by the number of RSVPs hoping to optimize our party enjoyment. We sort by rating on Amazon hoping to optimize our dollar. We scour Yelp and Foursquare to optimize the enjoyment of our meals. And product managers crunch numbers and run experiments to optimize their product decisions.

Take a minute to think about how the spreadsheet has changed your life. How often do you make a decision without researching how to optimize something?

This is not to say we shouldn’t use “spreadsheets” to optimize our decisions. We often do make better decisions through data analysis. Rather, what I think is interesting is just how significant our bias toward analytical reasoning has become. Our hammer is the spreadsheet, and now we’re making everything in product management a nail.

I’ve long been a believer that your environment significantly shapes the type of products you can build. Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful. When you’re building software, your environment is primarily made up of the tools and processes you use. And when I look at the processes that dominate our industry today — Agile/XP, Lean, Data-Driven — they have a common trait. They assume a lack of emotion — an overriding rationality of our customers.

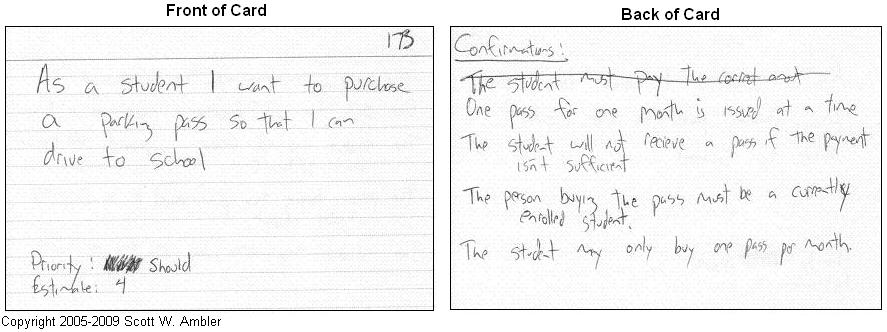

Think about Agile/XP User Stories. The original purpose of a User Story was to produce an estimate for work. But the unintended consequence is that User Stories have become a popular tool for product managers who believe they are communicating the perspective of customers. Why describe functionality when you can communicate what the customer wants?

But this is reality only by the numbers. I guarantee you that no one wants to purchase a parking pass. Many people want a parking pass, but no one wants to purchase it. This Story is useful as a feature requirement, but in no way does it communicate the perspective of the user. What would happen if we actually tried to communicate the perspective of a user?

Christine just got her second parking ticket this week. She walks up to her car and screams this is fucking bullshit! She admits to herself that she really does need to spend her Apple Watch money on a parking pass. Bullshit! She’s already dreading the lecture from her mother once she gets a copy of this ticket in the mail. But, she has to admit that she’s looking forward to the relief of parking without worrying about tickets. Still. No watch. Blergh.

Can you feel her anger and frustration? How does a User Story communicate this? It doesn’t. It assumes Christine is a golden child, birthed of pure rationality and light who simply does not drive to school without a parking pass.

What advantage does the User Story have if it is not communicating customer perspective? What value do we gain by saying As a student I want to purchase a parking pass so that I can drive to school over something more straightforward like Students can purchase a parking pass. We’ve gotten too analytical with our tools. We’ve bulldozed emotion without realizing what we were doing.

How might you change your design if your tools promoted an emotional understanding of Christine’s perspective? What if immediate purchase included a discount or forgiveness for the ticket itself? You might just end up with happier students and more parking passes sold.

Unfortunately, things get sticky when we leave our numbers behind. We’re not practiced at feeling emotion in a professional environment. We associate emotions with irrationality and poor decisions — something to be avoided. As an organization approaches Dunbar’s number, being vulnerable and feeling emotion becomes less and less safe. Our customers continue to feel and be swayed by emotion just like the rest of us while we’re busy building a world in where we don’t have to feel.

It’s time we revisited our tools with a focus on promoting emotional understanding. Our customers deserve it. And frankly, we’ve been fucking up their lives with our lack of empathy. I don’t have the complete answer, but I do have some suggestions.

-

Jobs to be Done

JTBD is my favorite software design tool of the past five years. But my favorite part is that it forces you to acknowledge the emotional aspect of why people use or don’t use your product. -

Regular one-on-ones with customers

Spend time with your customers where it’s all about them — without survey questions or a predefined conversation structure. You might even make a new friend. -

Customer stories

One thing Chrissie did while she was creating GitHub’s User Research department was to include stories of individual customers in all of our UXR studies. In the midst of data spanning thousands of customers and millions of records, there’d be a story about Alice’s feelings. This is what Alice thinks Pull Requests are. This is how she explains them with a crayon and a piece of paper. Stories about individuals carry tremendous power over our emotions. Think about how we are drawn to the characters in novels and TV shows. -

Use all of your product

Do you pay for your own product? Do you register for a new account on a regular basis? Do you use every screen, even if you don’t have a reason to? How often do you modify your account settings? You might be surprised at how much better you understand those snarky tweets if you set aside time to use your product for tasks you have no need to accomplish. -

Train your intuition

Don’t be bullied into the world view that every decision must be proven with data. Fed by enough meaningful experience, our intuitive reasoning is extremely powerful. Train your intuition, and learn how to communicate intuitive reasoning.

If we want to build better products, we must learn to include emotional understanding into our product decisions without resorting to analytical reasoning. Emotions must be felt.