You should take time to design your URL structure. If there’s one thing I hope you remember after reading this article it’s to take time to design your URL structure. Don’t leave it up to your framework. Don’t leave it up to chance. Think about it and craft an experience.

URL Design is a complex subject. I can’t say there are any “right” solutions — it’s much like the rest of design. There’s good URL design, there’s bad URL design, and there’s everything in between — it’s subjective.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t best practices for creating great URLs. I hope to impress upon you some best practices in URL design I’ve learned over the years and explain why I think new HTML5 javascript history APIs are so exciting to work with.

Why you need to be designing your URLs

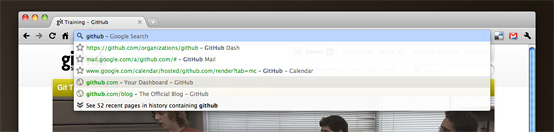

The URL bar has become a main attraction of modern browsers. And it’s not just a simple URL bar anymore — you can type partial URLs and browsers use dark magic to seemingly conjure up exactly the full URL you were looking for. When I type in resque issues into my URL bar, the first result is https://github.com/defunkt/resque/issues.

URLs are universal. They work in Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Internet Explorer, cURL, wget, your iPhone, Android and even written down on sticky notes. They are the one universal syntax of the web. Don’t take that for granted.

Any regular semi-technical user of your site should be able to navigate 90% of your app based off memory of the URL structure. In order to achieve this, your URLs will need to be pragmatic. Almost like they were a math equation — many simple rules combined in a strategic fashion to get to the page they want.

Top level sections are gold

The most valuable aspect of any URL is what lies at the top level section. In my opinion, it should be the first discussion of any startup directly after the idea is solidified. Long before any technology discussion. Long before any code is written. This is top-level section is going to change the fundamentals of how your site functions.

Do I seem dramatic? It may seem that way — but come 1,000,000 users later think about how big of an impact it will be. Think about how big of a deal Facebook’s rollout of usernames was. Available URLs are a lot like real estate and the top level section is the best property out there.

Another quick tip — whenever you’re building a new site, think about blacklisting a set of vanity URLs (and maybe learn a little bit about bad URL design from Quora’s URLs).

Namespacing is a great tool to expand URLs

Namespaces can be a great way to build up a pragmatic URL structure that’s easy to remember with continued usage. What do I mean by a namespace? I mean a portion of a URL that dictates unique content. An example:

https://github.com/defunkt/resque/issuesIn the URL above, defunkt/resque is the namespace. Why is this useful? Because anything after that URL suddenly becomes a new top level section. So you can go to any <user>/<repo> and then tack on /issues or maybe /wiki and get the same page, but under a different namespace.

Keep that namespace clean. Don’t start throwing some content under /feature/<user>/<repo> and some under /<user>/<repo>/feature. For a namespace to be effective it has to be universal.

Querystrings are great for filters and sorts

The web has had a confused past with regards to querystrings. I’ve seen everything from every page of a site being served from one URL with different querystring parameters to sites who don’t use a single querystring parameter.

I like to think of querystrings as the knobs of URLs — something to tweak your current view and fine tune it to your liking. That’s why they work so great for sorting and filtering actions. Stick to a uniform pattern (sort=alpha&dir=desc for instance) and you’ll make sorting and filtering via the URL bar easy and rememberable.

One last thing regarding querystrings: The page should work without the querystrings attached. It may show a different page, but the URL without querystrings should render.

Non-ASCII URLs are terrible for english sites

The world is a complicated place filled with ¿ümlÃ¥ts?, ¡êñyés! and all sorts of awesome characters ☄. These characters have no place in the URL of any english site. They’re complicated to type with english keyboards and often times expand into confusing characters in browsers (ever see xn--n3h in a url? That’s a ☃).

URLs are for humans — not for search engines

I grew up in this industry learning how to game search engines (well, Google) to make money off my affiliate sales, so I’m no stranger to the practice of keyword stuffing URLs. It was fairly common to end up with a URL like this:

http://guitars.example.com/best-guitars/cheap-guitars/popular-guitar

That kind of URL used to be great for SEO purposes. Fortunately Google’s hurricane updates of 2003 eliminated any ranking benefit of these URLs. Unfortunately the professional SEO industry is centered around extortion and still might advise you stuff your URLs with as many keywords as you can think of. They’re wrong — ignore them.

Some additional points to keep in mind:

Underscores are just bad. Stick to dashes.

Use short, full, and commonly known words. If a section has a dash or special character in it, the word is probably too long.

URLs are for humans. Design them for humans.

A URL is an agreement

A URL is an agreement to serve something from a predictable location for as long as possible. Once your first visitor hits a URL you’ve implicitly entered into an agreement that if they bookmark the page or hit refresh, they’ll see the same thing.

Don’t change your URLs after they’ve been publicly launched. If you absolutely must change your URLs, add redirects — it’s not that scary.

Everything should have a URL

In an ideal world, every single screen on your site should result in a URL that can be copy & pasted to reproduce the same screen in another tab/browser. In fairness, this wasn’t completely possible until very recently with some of the new HTML5 browser history Javascript APIs. Notably, there are two new methods:

onReplaceState— This method replaces the current URL in the browser history, leaving the back button unaffected.onPushState– This method pushes a new URL onto the browser’s history, replacing the URL in the URL bar and adding it to the browser’s history stack (affecting the back button).

When to use onReplaceState and when to use onPushState

These new methods allow us to change the entire path in the URL bar, not just the anchor element. With this new power, comes a new design responsibility — we need to craft the back button experience.

To determine which to use, ask yourself this question: Does this action produce new content or is it a different display of the same content?

Produces new content — you should use

onPushState(ex: pagination links)Produces a different display of the same content — you should use

onReplaceState(ex: sorting and filtering)

Use your own judgement, but these two rules should get you 80% there. Think about what you want to see when you click the back button and make it happen.

A link should behave like a link

There’s a lot of awesome functionality built into linking elements like <a> and <button>. If you middle click or command-click on them they’ll open in new windows. When you hover over an <a> your browser tells you the URL in the status bar. Don’t break this behavior when playing with onReplaceState and onPushState.

Embed the location of AJAX requests in the

hrefattributes of anchor elements.return truefrom Javascript click handlers when people middle or command click.

It’s fairly simple to do this with a quick conditional inside your click handlers. Here’s an example jQuery compatible snippet:

$('a.ajaxylink').click(function(e){

// Fallback for browser that don't support the history API

if (!('replaceState' in window.history)) return true

// Ensure middle, control and command clicks act normally

if (e.which == 2 || e.metaKey || e.ctrlKey){

return true

}

// Do something awesome, then change the URL

window.history.replaceState(null, "New Title", '/some/cool/url')

return false

})

Post-specific URLs need to die

In the past, the development community loved to create URLs which could never be re-used. I like to call them POST-specific URLs — they’re the URLs you see in your address bar after you submit a form, but when you try to copy & pasting the url into a new tab you get an error.

There’s no excuse for these URLs at all. Post-specific URLs are for redirects and APIs — not end-users.

A great example

ASCII-only user generated URL parts (defunkt, resque).

“pull” is a short version of “pull request” — single word, easily associated to the origin word.

The pull request number is scoped to defunkt/resque (starts at one there).

Anchor points to a scrolling position, not hidden content.

Bonus points: This URL has many different formats as well — check out the patch and diff versions.

The beginning of an era

I hope that as usage of new Javascript APIs increases, designers and developers take time to design URLs. It’s an important part of any site’s usability and too often I see URLs ignored. While it’s easy to redesign the look & feel of a site, it’s much more difficult to redesign the URL structure.

But I’m excited. I’ve watched URLs change over the years. At times hard-linking was sacrificed at the altar of AJAX while other times performance was sacrificed to generate real URLs for users. We’re finally at a point in time where we can have the performance and usability benefits of partial page rendering while designing a coherent and refined URL experience at the same time.